A mind mapping-based literature review on urban

renewal

Joseph Kim-keung Ho

Independent Trainer

Hong Kong, China

Abstract: The topic of urban renewal is a main one

in housing studies. This article makes use of the mind mapping-based literature

review (MMBLR) approach to render an image on the knowledge structure of urban

renewal. The finding of the review exercise is that its knowledge structure

comprises six main themes, i.e., (a) Meanings of urban

renewal, (b) Main approaches on urban renewal, (c) Specific urban renewal practices, (d) Main conceptual

themes related to urban renewal, (e)

Trends and drivers of urban renewal and, finally, (f) Controversies and issues

of urban renewal. There is also a set of key concepts identified from the urban

renewal literature review. The

article offers some academic and pedagogical values on the topics of urban

renewal, literature review and the mind mapping-based literature review (MMBLR)

approach.

Key

words: Urban renewal, literature

review, mind map, the mind mapping-based literature review (MMBLR) approach

Introduction

Urban

renewal is a main topic in housing

studies. It is of academic and pedagogical interest to the writer who has been

a lecturer on housing studies for some tertiary education centres in Hong Kong.

In this article, the writer presents his literature review findings on housing

studies using the mind mapping-based literature review (MMBLR) approach. This

approach was proposed by this writer this year and has been employed to review

the literature on a number of topics, such as supply chain management,

strategic management accounting and customer relationship management (Ho,

2016). The MMBLR approach itself is not particularly novel since mind mapping

has been employed in literature review since its inception. The overall aims of

this exercise are to:

1. Render an image of the knowledge structure of

urban renewal via the application of the MMBLR approach;

2. Illustrate how the MMBLR approach can be

applied in literature review on an academic topic, such as urban renewal.

The findings from this

literature review exercise offer academic and pedagogical values to those who

are interested in the topics of urban renewal, literature review and the MMBLR

approach. Other than that, this exercise facilitates this writer’s intellectual

learning on these three topics. The next section makes a brief introduction on

the MMBLR approach. After that, an account of how it is applied to study urban

renewal is presented.

On mind mapping-based literature review

The mind mapping-based

literature review (MMBLR) approach was developed by this writer this year (Ho,

2016). It makes use of mind mapping as a complementary literature review

exercise (see the Literature on mind

mapping Facebook page and the Literature

on literature review Facebook page). The approach is made up of two steps.

Step 1 is a thematic analysis on the literature of the topic chosen for study.

Step 2 makes use of the findings from step 1 to produce a complementary mind

map. The MMBLR approach is a relatively straightforward and brief exercise. The

approach is not particularly original since the idea of using mind maps in

literature review has been well recognized in the mind mapping literature. The

MMBLR approach is also an interpretive exercise in the sense that different

reviewers with different research interest and intellectual background

inevitably will select different ideas, facts and findings in their thematic

analysis (i.e., step 1 of the MMBLR approach). Also, to conduct the approach,

the reviewer needs to perform a literature search beforehand. Apparently, what

a reviewer gathers from a literature search depends on what library facility,

including e-library, is available to the reviewer. The next section presents

the findings from the MMBLR approach step 1; afterward, a companion mind map is

provided based on the MMBLR approach step 1 findings.

Mind mapping-based literature review on urban renewal:

step 1 findings

Step 1 of the MMBLR approach is

a thematic analysis on the literature of the topic under investigation (Ho,

2016). In our case, this is the urban renewal topic. The writer gathers some academic

articles from some universities’ e-libraries, books on urban renewal as well as

via the Google Scholar. With the academic articles collected, the writer

conducted a literature review on them to assemble a set of ideas, viewpoints,

concepts and findings (called points here). The points from the urban renewal literature

are then grouped into six themes here. The key words in the quotations are

bolded in order to highlight the key concepts involved.

Theme 1: Meanings of urban renewal

Point 1.1.

“By urban renewal, we

refer to a multiscalar process of

regulatory change, undertaken to facilitate rapid land and property

redevelopment in central city areas” (Weinstein

and Ren, 2009);

Point 1.2.

“In a narrow

sense urban renewal

addresses the processes which influence the condition of the city’s physical

plant. The plant ages, becomes obsolescent, and is consumed in the production

of shelter and other services. It is also constantly being renewed through the market processes in the form of capital replacement investment” (Wingo Jr, 1966);

Point 1.3.

“The term urban renewal was introduced in France

in the Loi solidarite’ et

renouvellement urbains (Loi SRU) of

December 13th, 2000. Until then, terms like renovation, reconstruction,

recycling or refurbishment were used to indicate similar phenomena..... It

appears that ever since its introduction in 2000, the notion of urban renewal

has been subject to variations in its meaning and in its implementation” (Bonneville,

2005);

Point 1.4.

“For much of the 20th century, the

people who cared most about the health and form of cities in the USA –

including city planners, government officials, and downtown businessmen –

considered dilapidated and deteriorating neighborhoods as among the most vexing

of problems. The solution they chose was ‘‘urban renewal,’’ a term which today

is commonly understood to mean the government

program for acquiring, demolishing, and replacing buildings deemed slums.

In fact, the original meaning of the term ‘‘urban renewal’’ was quite

different” (Von Hoffman, 2008);

Point 1.5.

“In the case of urban renewal in

Turkey, marketization has both a spatial and a temporal aspect. Urban renewal

aims to incorporate spontaneously developed and partially regulated spaces into

the formal circuits of capital

accumulation by replacing unauthorized substandard housing with fully legal

and certified housing units” (Karaman, 2013);

Point 1.6.

“There is an immense literature

on informal housing, slum clearance and organized struggles around the right to

housing. A common thread running through all these debates is the ways in which

urban renewal has been used as a tool of

dispossession, expropriating residents and uprooting them from their social

networks” (Karaman, 2013);

Point 1.7.

“Urban

renewal decision-making, then, focuses on the older parts of the region, while

treating them in the context of overall regional development. The phenomena

with which it must deal are essentially aspects of the intrametropolitan

processes at work shaping the spatial organization of the metropolitan region”

(Wingo Jr, 1966);

Point 1.8.

“Urban renewal is a complex process that has been

commonly adopted to cope with changing urban environment, to rectify the

problem of urban decay and to meet

various socioeconomic objectives” (Lee and

Chan, 2008);

Point 1.9.

“Urban

renewal is not just renewing buildings; more is renewing city economy,

transportation, education and other aspects” (Ou and Wu, 2014);

Point 1.10.

“The fundamental goal of urban renewal is to carry

out reconstruction, refurbishment, and maintenance in the context of urban planning to promote the

sustainable use of the overall environment and to improve environmental quality

and quality of life. Urban renewal itself consists of the replanning and

re-designing of older urban areas for more efficient use while simultaneously

bringing about a rise in housing prices in the affected areas” (Lee,

Liang and Chen, 2016);

Point 1.11.

“Urban renewal refers to the specific

stage of city development, the process and model of development and utilization

of city land” (Ou and Wu, 2014);

Theme 2: Main approaches of urban renewal

Point 2.1.

“….. In policy circles there have

been three broad approaches to tackling the ‘slum problem’. The oldest approach, slum clearance … entails the complete eradication of an existing

slum, often supplemented by a program of resettlement into public housing….. … Tenure legalization emerged as a second

approach in …This involves the provision of legal title to urban informal and

illegal settlements... Since the late 1980s, ‘property-led redevelopment’ has emerged as the dominant paradigm …

This approach relies on real estate development as the driving force for urban

regeneration” (Karaman, 2013);

Point 2.2.

“…a

review of the laws SRU and Borloo on the one hand, and the observation of the

practice of urban renewal on the other, indicate two different approaches to

urban renewal that exist alongside each other…. The first approach is to be

found in operations of urban renewal realised in line with a logic of

reinserting the areas into the land and real estate market… The second approach is to be found in

operations officially labelled urban renewal. These concern almost exclusively

areas of degraded social housing in large high-rise housing estates. This

approach shows more continuity with earlier interventions, which privileged a

social approach to urban renewal …. In

some cases, the two types of urban renewal are mixed” (Bonneville,

2005);

Point 2.3.

“In

Dutch urban renewal, we observe an implementation

gap between dreaming and doing. Dutch national government recently proposed

to focus urban renewal on more than 50 priority areas in the cities and to

reduce urban renewal subsidies. It is not very likely that this policy will

accelerate urban renewal. This contribution suggests a different approach: the

formulation of an urban district vision shared by the sustainable stakeholders

in those districts” (Priemus, 2004);

Theme 3: Specific urban renewal practices

Point 3.1.

“…Public–private partnership in urban renewal in France concerns mainly

housing, transport infrastructure and large public facilities. The distinction

between public, private and civil actors does not concern social and economic

development. This situation tends to limit the integration of different issues

and approaches in renewal projects. Also, French urban renewal projects do not

produce a new type of partnership between public and private actors and the

regulatory framework” (Dormois, Pinson and Reignier, 2005);

Point 3.2.

“Entrepreneurial

policies have been widely accepted as a panacea for post-industrial urban

decline in North American and Western European cities. However, scholars

reporting on the disempowering consequences of zero-sum competition and

trickledown economic policies have shown that entrepreneurial policies have had

limited success in generating economic growth and employment, and have in many

instances exacerbated social divisions and inequalities …. In addition, the

‘spill-over effects’ of flagship projects have been rarely observed” (Karaman,

2013);

Point 3.3.

“The [Hong Kong] Government’s intention in changing the

institutional arrangements in relation to the control of property rights was to provide an additional incentive for the

private developers by reducing uncertainty in the land assembly process” (Hastings

and Adams, 2005);

Point 3.4.

“To

a certain extent, the Chinese construction industry can be characterized by the

substantial demolition and rebuilding

works in urban areas” (Shen, Yuan and Kong, 2013);

Point 3.5.

“To define the physical form of an urban area fulfilling the sustainable development objectives,

Planning Department [in Hong Kong] has issued urban design guidelines, which

underpin the future urban development directions of Hong Kong. They emphasize

the importance of urban design and address issues like development height

profile, waterfront development, cityscape, pedestrian environment and

pollution mitigation” (Chan and Lee, 2008);

Point 3.6.

“[In Hong Kong] The adoption of a tenants-in-common property rights system has had far reaching

implications for the process of assembling land held in multiple ownership. In

order for redevelopment to take place, it is necessary to acquire all the

interests in a property, but for the private sector this is entirely dependent

on negotiating agreement and any individual owner can prevent the process by

refusing to vote their block of shares. In these circumstances, private

developers often face extended negotiations and unrealistic highly expectations

as to values, resulting in delays in the land assembly process” (Hastings

and Adams, 2005);

Point 3.7.

“….urban renewal policy in France is not limited to the operations

labelled as such by central administrations handing out subsidies and dealing

with peripheral social housing estates. Local authorities also launched their

own urban renewal programmes mobilising a large diversity of public and

semi-public funds. These programmes do not only target large peripheral social

housing estates but also central or semi-central boroughs still characterised

by a degradation of housing estates and by their proximity to the main loci of

estate market valorisation, i.e. the city centres” (Dormois, Pinson and Reignier, 2005);

Point 3.8.

“…an information system for urban renewal decision-making can

build on the state of knowledge of intraregional processes and the special

informational requirements of urban renewal decisions” (Wingo Jr, 1966);

Point 3.9.

“…in 1999, as

part of the wider changes to the institutional environment, [the Hong Kong

Government] introduced the Land (compulsory sale for redevelopment) Ordinance

Cap545 which, it was believed, would facilitate land assembly by the private

sector and thereby encourage greater interest in the area of urban renewal” (Hastings

and Adams, 2005);

Point 3.10.

“…the application of the concept of sustainable urban design is not limited

to urban development projects. This idea has also been introduced to local

urban renewal practices recently [in Hong Kong]” (Chan

and Lee, 2008);

Point 3.11.

“…the evolution of

public policy [on urban renewal] has shifted the policy focus from the slum

area to the neighborhood, to the central city, and ultimately to the region;

from limited concerns with the lowest housing strata to the total housing stock

and even to the state of the physical plant of the region; from a policeman-and

policed relationship between local governments and parts of the private housing

sector to an intricate net of public-private relations into which are drawn

neighborhood organizations, financial institutions, welfare agencies, local

interest groups, and the complex an ay of housing, planning, land use, and

transportation agencies from every level of government” (Wingo Jr, 1966);

Point 3.12.

“Although the Urban Renewal Authority chooses to negotiate with

affected parties, the power to implement resumption procedures without the

requirement of meeting a 90 per cent ownership

threshold ensures that land assembly is less of an issue” (Hastings

and Adams, 2005);

Point 3.13.

“In Hong Kong, the major public agency involved in the urban

process is the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA)… But in addition to the

public agencies, the Government has always encouraged private sector involvement in the renewal process” (Hastings

and Adams, 2005);

Point 3.14.

“Land and housing reforms

are the key institutional mechanisms that have facilitated urban renewal in

China and have been the focus on numerous studies” (Weinstein and Ren, 2009);

Point 3.15.

“Squatting as a

housing strategy and as a tool of urban social movements accompanies the

development of capitalist cities worldwide.…. the dynamics of squatter

movements are directly connected to strategies of urban renewal in that

movement conjunctures occur when urban regimes are in crisis” (Holm

and Kuhn, 2011);

Point 3.16.

“The design and execution of urban

projects under an entrepreneurial regime

of governance are oriented towards development of particular places through

often spectacular projects — the primary aim of which is the upgrading of the

image of a locality—as opposed to comprehensive planning aimed at improving

living or working conditions within a larger juridical context” (Karaman,

2013);

Point 3.17.

“The new institutional arrangement

[the Land (compulsory sale for redevelopment) Ordinance, one of a series of

urban renewal policy initiatives introduced by the Hong Kong Government] was mooted as a means to facilitate greater

private sector participation in the

renewal process by overcoming existing constraints on land assembly, which

arise as the result of a system of common property ownership” (Hastings

and Adams, 2005);

Point 3.18.

“Urban renewal in South Africa involves contending with a

combination of high crime rates,

increasing inequality and growing public frustration” (Samara, 2005);

Theme 4: Main conceptual themes related to urban

renewal

Point 4.1.

“A project [e.g. a urban renewal project] is said to

be socially sustainable when it

creates harmonious living environment, reduces social inequality and cleavages,

and improves quality of life in general” (Chan and Lee, 2008);

Point 4.2.

“As it [urban entrepreneurialism]

fundamentally hinges on public–private

partnerships, privatization of

publicly owned assets and deregulated

spatial development, it is very much insulated from public accountability

and is therefore effectively anti-democratic” (Karaman,

2013);

Point 4.3.

“..it is generally agreed that economy, environment and social equity

are three foremost components of sustainability

concept” (Chan and Lee, 2008);

Point 4.4.

“….The field of urban planning

strongly values the ideals of public

participation and public debate. However, during much of the twentieth

century, urban planning seldom acknowledged the needs or desires of the public

to shape their own communities’ futures. During the 1950s and 1960s, many

federal planning programs, including urban renewal and highway construction,

destroyed vibrant urban neighborhoods despite strong neighborhood opposition” (Tighe

and Opelt, 2016);

Point 4.5.

“As large cities

concentrate both the most advanced service sectors and a large marginalized population, cities have

become a setting for new citizenship

practices to emerge. Here she makes a distinction between power and

presence, arguing that powerless political groups can still produce presence

and gain visibility by claiming rights to the city” (Weinstein and Ren, 2009);

Point 4.6.

“Foreign scholars study about urban renewal

generally focuses on the following aspects: (1) Exploration and practice of

urban renewal…(2) The study of city renewal evolution law…. (3) City sociology

study on environmental behavior of human space…. (4) Study on mixed mode

of urban renewal…” (Ou and Wu, 2014);

Point 4.7.

“Frequently recast in the

frame of global and globalizing cities, more recent inquiries into residential

displacements and housing rights have tended to employ a political economy perspective, examining the decisions of

governments, local elites, and those acting on behalf of global capital to

promote higher value land uses, thus facilitating the residential and

employment displacement of the city’s lower income residents” (Weinstein and Ren, 2009);

Point 4.8.

“It is clearly not coincidental that characteristics of the

metropolitan social structure are closely related to the condition and rate of

replacement of the region’s housing stock-poor people, for example, consume

only the dwelling services of a deteriorating, obsolete segment of the stock.

The relationship between marginal firms and old, poorly maintained commercial

structures is similarly clear. Because there tend to be concentrations of such

deteriorated structures in the city, the “problem” of blight exists” (Wingo Jr, 1966);

Point 4.9.

“Recent theoretical

inquiries into urban citizenship

have made important contributions to understanding the social consequences of

urban renewal” (Weinstein and Ren, 2009);

Point 4.10.

“Recently, sustainable urban

design has gained popularity to deal with the problems and to increase

positive outcomes of urban renewal projects … This approach intends to take

into account of the sustainability concept when designing the projects in order

to create sustainable communities for the citizens” (Chan

and Lee, 2008);

Point 4.11.

“The concept of sustainable

development was defined by World Commission on Environment and Development

(WCED) as ‘‘a development that meets the needs of the present generation

without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own

needs’’ in 1987” (Chan and Lee, 2008);

Point 4.12.

“The concept of sustainable

urban design ….. refers to a process in which sustainability concept is

taken into account when deciding which urban design features should be

incorporated into urban (re)development plans” (Chan and Lee,

2008);

Point 4.13.

“The main goals of community participation [in urban renewal projects] are to ‘empower the residents, to build beneficiary

capacity, to increase project effectiveness, to improve project efficiency and

to share project costs’…” (Kotze

and Mathola, 2012);

Point 4.14.

“A broader construction of the urban

renewal problem would embrace the critical

ecological dimensions which accompany the differential rates of replacement

of the plant in various parts of the city” (Wingo

Jr, 1966);

Point 4.15.

“Cities, like businesses, are seen as being in competition with

each other for securing or defending their share of the global market …. urban

entrepreneurialism has been widely promoted to urban policymakers as the only

viable solution. Urban

entrepreneurialism denotes an array of governance mechanisms and policies

aimed at nurturing local and regional economic growth by creating a business

environment favorable to capital investment and accumulation ...” (Karaman,

2013);

Theme 5: Trends and drivers of urban renewal

Point 5.1.

“….Since the late nineteenth century, urban renewal programmes have focused

on improving housing for the poor, marginalised urban population …. These

programmes invariably embody slum clearance, the replacement of dilapidated

housing structures with new subsidised housing units, and also make provision

for infrastructural development, schools and other amenities… From an

international perspective, this transformation process varies from city to

city, but the overall trend allegedly reduces the gap between the rich and the

poor within cities …” (Kotze and Mathola, 2012);

Point 5.2.

“Although not without its successes, the notion of

urban renewal became deeply unpopular by the late 1960s not just among those

who were displaced but also with those concerned about the profound social

consequences of that displacement for the city and wider society” (Gold, 2012);

Point 5.3.

“European cities are currently

facing problems of social and economic decline and physical decay, but they

also put attractiveness and development issues on their agenda. In this

context, the objective of urban renewal projects is to attract new firms or

high-income households …. Urban renewal projects are seen as part of a broader growth-oriented strategy shaped by

local elites to re-image their cities in

an increasingly competitive urban system” (Dormois, Pinson

and Reignier, 2005);

Point 5.4.

“In

recent years, there is significant growth in the interest of merging sustainability concept into urban (re)development policies through urban design skill” (Chan and Lee, 2008);

Point 5.5.

“In South Africa, the spatial legacy of Apartheid

has resulted in township areas that can be recognised as intense concentrations

of poverty. Variations in the types of housing, often dominated by informal

structures and overcrowded conditions, are characteristic of these areas. As

such, they are generally perceived as areas of limited economic potential. In

response to these conditions and in an attempt to alleviate the associated

problems, the African National Congress government has initiated an Urban Renewal

Programme in eight nodes in six urban areas in the country” (Kotze

and Mathola, 2012);

Point 5.6.

“The growth of urbanization

in China has resulted in a large amount of housing demand throughout the

country, inducing a huge number of construction projects in urban areas. These

housing demands can be commonly met through urban sprawl development and urban

renewal” (Shen, Yuan and Kong, 2013);

Point 5.7.

“The

problem of urban decay in Hong Kong is getting worse recently; therefore, the

importance of urban renewal in improving the physical environment conditions

and the living standards of the citizens is widely recognized in the territory.

However, it is not an easy task for the Hong Kong Government to prepare welcome

urban renewal proposals because the citizens, professionals and other concerned

parties have their own expectations

which are difficult to be addressed all at the same time” (Lee

and Chan, 2008);

Point 5.8.

“the two terms used most commonly in discourse

about urban change in the two decades after the Second World War were undoubtedly

reconstruction’ and ‘renewal’..” (Gold,

2012);

Theme 6: Controversies and issues of urban

renewal

Point 6.1.

“Urban renewal may be the most

universally vilified program in planning history, remembered primarily for

its destruction of established, central, urban neighborhoods along with the

construction of isolated, peripheral, housing projects” (Tighe

and Opelt, 2016);

Point 6.2.

“…a useful restatement of the policy problem of

urban renewal would shift the emphasis away from efforts to arrest blight

directly and toward the determination of how much and what kinds of community

actions should be taken to achieve specified levels of conservation of the

physical plant of the community” (Wingo

Jr, 1966);

Point 6.3.

“…the

use of social differences to

distribute rights to different categories of citizens produces a differentiated

or disjunctive citizenship” (Weinstein

and Ren, 2009);

Point 6.4.

“A number of authors …. have examined the urban renewal process in

Hong Kong. In each case the authors identified the problem of land assembly as an underlying constraint of the success

to redevelopment projects” (Hastings and Adams, 2005);

Point 6.5.

“Despite the fact that the importance of buildings’ lifespan has been well

addressed in previous studies, buildings’ short lifespan as a result of urban

renewal in China has been hitherto given little attention” (Shen,

Yuan and Kong, 2013);

Point 6.6.

“Determining

a sustainable [urban] renewal proposal

is a difficult and complicated process because a lot of tradeoff decisions have

to be made” (Lee and Chan, 2008);

Point 6.7.

“In both Shanghai and

Mumbai, large swaths of urban land have been privatized or leased to private

developers for redevelopment. Amidst increased pressures to attract capital

investment, and to position their cities as global ones, governments, operating

at multiple geopolitical scales, have taken often brutal measures to remove residents and clear land. In the process,

the rights to housing and livelihoods for millions of city residents are being

dismantled” (Weinstein and Ren, 2009);

Point 6.8.

“In Hong Kong, numbers of urban renewal projects have been

conducted but many of them fail to achieve their goals and generate

environmental and social problems in the community … Some people argue that

this phenomenon is probably due to poor quality of the urban renewal proposals” (Lee and

Chan, 2008);

Point 6.9.

“In urban renewal, as elsewhere, there is a gap between the idea and the reality,

between the conception and the creation. Throughout the country there are

communities with renewal programs that show no material indications of their

existence, except perhaps a hole in the ground. In other communities “something

has happened”; their “success” is indicated by the clearance of blighted areas

and new construction. But the renewed areas seem to bear little resemblance to

the initial visions as they appeared in the blueprints of the planners or the

pictures in the glossy brochures” (Bellush

and Hausknecht, 1966);

Point 6.10.

“One of the difficulties in probing the rationale of urban

renewal policy is the lack of consensus

about both what the program is and what it ought to be. It certainly began as a

housing program: its antecedents were instituted in large degree to improve the

welfare of the low income consumers of housing services. Other interests have

injected new viewpoints and objectives which have diluted considerably the

housing goals” (Wingo Jr, 1966);

Point 6.11.

“Over time different developers will have gained experience and

developed their own areas of expertise. Since operating in a familiar

environment increases the frequency of operation and reduces transaction costs,

the introduction of a new institutional mechanism may be of little interest to

developers who do not chose to assemble

land in this way” (Hastings and Adams, 2005);

Point 6.12.

“Regardless of the evolution of participatory

planning theory, memories of past planning mistakes and oversights continue

to impede planners. Consequently, planners must try to move forward and beyond

their predecessors’ mistakes while simultaneously taking responsibility for

them so as not to seem indifferent to or apathetic to the harm done” (Tighe

and Opelt, 2016);

Point 6.13.

“The current urban renewal

programs in some developing countries, such as China, are at the expense of

demolishing a huge number of existing buildings without distinction. As a

consequence, the buildings’ short lifespan due to premature demolition and

resultant adverse impacts on environment and society have been criticized for

not being in line with sustainable

development principles” (Shen, Yuan and Kong, 2013);

Point 6.14.

“Urban renewal is commonly adopted to cope with changing urban

environment, to rectify the problem of urban decay and to meet various socio-economic objectives … However,

the urban renewal projects are often beset with social problems such as

destruction of existing social networks, expulsion of vulnerable groups and

adverse impacts on living environments” (Chan and Lee, 2008);

Point 6.15.

”Most previous studies have discussed urban renewal issues in

terms of legal systems, operational methods, and case studies. The impact of

urban renewal on neighbourhood housing

prices, however, has rarely been discussed” (Lee,

Liang and Chen, 2016);

Point 6.16.

“…in French renewal projects, the private actors

involved in the partnership with local authorities remain the ‘‘usual

suspects’’: the property developers and the main landowners, the local

private–public society and the regional banks (Heinz, 1994). Yet, these ‘‘powerful’’

private actors often see their intervention limited to the provision of

resources in order ‘‘to fill’’ a project pre-elaborated by public planners and

bureaucrats. As a consequence, the traditional domination of public regulations (regulatory imposition,

legal sanction of public choices) is not challenged” (Dormois, Pinson and Reignier, 2005);

Each of them has a set of

associated points (i.e., idea, viewpoints, concepts and findings). Together

they provide an organized way to comprehend the knowledge structure of the urban

renewal topic. The bolded key words in the quotation reveal, based on the

writer’s intellectual judgement, the key concepts examined in the urban renewal

literature. The referencing indicated on the points identified informs the

readers where to find the academic articles to learn more about the details on

these points. Readers are also referred to the urban development and redevelopment Facebook page for more

information on the urban renewal topic. The process of conducting the thematic

analysis is an exploratory as well as synthetic learning endeavour on the

topic’s literature. Once the structure of the themes, sub-themes[1]

and their associated points are finalized, the reviewer is in a position to

move forward to step 2 of the MMBLR approach. The MMBLR approach step 2

finding, i.e., a companion mind map on urban renewal, is presented in the next

section.

Mind mapping-based literature review on urban renewal:

step 2 (mind mapping) output

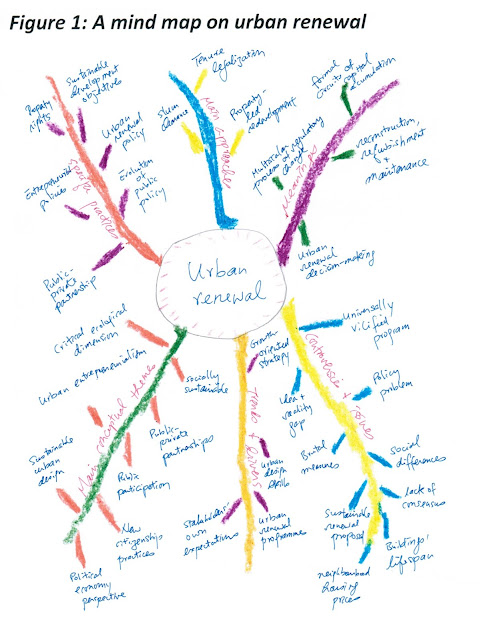

By adopting the findings from

the MMBLR approach step 1 on urban renewal, the writer constructs a companion

mind map shown as Figure 1.

Referring to the mind map on urban

renewal, the topic label is shown right at the centre of the map as a large

blob. Six main branches are attached to it, corresponding to the six themes

identified in the thematic analysis. The links and ending nodes with key

phrases represent the points from the thematic analysis. The key phrases have

also been bolded in the quotations provided in the thematic analysis. As a

whole, the mind map renders an image of the knowledge structure on urban

renewal based on the thematic analysis findings. Constructing the mind map is

part of the learning process on literature review. The mind mapping process is

speedy and entertaining. The resultant mind map also serves as a useful

presentation and teaching material. This mind mapping experience confirms the

writer’s previous experience using on the MMBLR approach (Ho, 2016). Readers

are also referred to the Literature on

literature review Facebook page and the Literature

on mind mapping Facebook page for additional information on these two

topics.

Concluding remarks

The MMBLR approach to study urban

renewal provided here is mainly for its practice illustration as its procedures

have been refined via a number of its employment on an array of topics (Ho,

2016). No major additional MMBLR steps nor notions have been introduced in this

article. In this respect, the exercise reported here primarily offers some

pedagogical value as well as some systematic and stimulated learning on urban

renewal. Nevertheless, the thematic findings and the image of the knowledge

structure on urban renewal in the form of a mind map should also be of academic

value to those who research on this topic.

Bibliography

1.

Bellush, J. and M. Hausknecht. 1966.

Entrepreneurs and urban renewal” Journal

of the American Institute of Planners 32(5) 289-297 (DOI:

10.1080/01944366608978210).

2.

Bonneville, M. 2005. “The

ambiguity of urban renewal in France: Between continuity and rupture” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment

20, Springer: 229-242.

3.

Chan, E. and G.K.L. Lee. 2008. “Critical factors for improving social

sustainability of urban renewal projects” Soc

Indic Res 85, Springer: 243-256.

4. Dormois, R., G. Pinson and H. Reignier. 2005. “Path-dependency

in public-private partnership in French urban renewal” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 20, Springer: 243-256.

5.

Gold, J.R. 2012. “A SPUR to action?:

The Society for the Promotion of Urban Renewal, ‘anti-scatter’ and the crisis

of city reconstruction, 1957–1963” Planning

Perspectives 27(2): 199-223 (DOI: 10.1080/02665433.2012.646770).

6.

Hastings, E.M. and D. Adams. 2005. “"Facilitating

urban renewal" Property Management

23(2):110 – 121.

7.

Ho,

J.K.K. 2016. Mind mapping for literature

review – a ebook, Joseph KK Ho publication folder October 7 (url address: http://josephkkho.blogspot.hk/2016/10/mind-mapping-for-literature-review-ebook.html).

8.

Holm, A.J. and A. Kuhn.

2011. “Squatting and Urban Renewal: The Interaction of Squatter Movements and

Strategies of Urban Restructuring in Berlin” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35(3) May:

644-658.

9.

Karaman, O. 2013.

“Urban Renewal in Istanbul: Reconfigured Spaces, Robotic Lives” International Journal of Urban and Regional

Research 37(2) March, Blackwell Publishing: 715-733.

10. Kotze, N. and A. Mathola. 2012. “Satisfaction Levels and the

Community’s Attitudes Towards Urban Renewal in Alexandra, Johannesburg” Urban Forum: 23: 245-256.

11.

Lee, C.C., C.M. Liang and C.Y. Chen. 2016. “The impact of urban

renewal on neighbourhood housing prices in Taipei: an application of the

difference-in-difference method” J Hous

and the Built Environ May 28, published online, Springer (DOI

10.1007/s10901-016-9518-1)

12. Lee, G.K.L. and E.H.W. Chan. 2008. “The Analytic Hierarchy Process

(AHP) Approach for Assessment of Urban Renewal Proposals” Soc. Indic Res 89: 155-168.

13.

Literature on literature review Facebook page, maintained by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address:

https://www.facebook.com/literature.literaturereview/).

14.

Literature on mind mapping Facebook page, maintained by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address: https://www.facebook.com/literature.mind.mapping/).

15.

Lowdon Wingo Jr., L. 1966. “Urban

renewal: a strategy for information analysis” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 32(3): 143-154 (DOI:

10.1080/01944366608978198).

16.

Ou, G. and G. Wu. 2014. “Chapter 16: Theory and Practice of Urban

Renewal: A Case Study of Hong Kong and

Shenzen” in D. Yang and Y. Qian (eds.) Proceedings

of the 18th International Symposium on Advancement of Construction Management

and Real Estate: 147-153 (DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-44916-1_16, ©

Springer-Verlag

Berlin Heidelberg 2014).

17. Priemus, H. 2004. “The path to

successful urban renewal: Current policy debates in the Netherlands” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment

19, Kluwer Academic Publishers: 199-209.

18.

Samara, T.R. 2005. “Youth, Crime and

Urban Renewal in the Western Cape” Journal

of Southern African Studies 31(1): 209-227 (DOI:

10.1080/03057070500035943).

19. Shen, L.Y., Yuan, H.P. and X.F. Kong. 2013. “Paradoxical

phenomenon in urban renewal practices: promotion of sustainable construction

versus buildings’ short lifespan” International

Journal of Strategic Property Management 17(4) Routledge: 377-389.

20.

Tighe, J.R. and T.J. Opelt. 2016. “Collective Memory and Planning:

The Continuing Legacy of Urban Renewal in Asheville, NC” Journal of Planning History 15(1), Sage: 46-67.

21.

Urban

development and redevelopment Facebook page, maintained

by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address: https://www.facebook.com/Urban-development-and-redevelopment-1729778137279385/).

22.

Von Hoffman. A. 2008. “The lost

history of urban renewal” Journal of

Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 1(3):

281-301 (DOI: 10.1080/17549170802532013).

23.

Weinstein, L. and X. Ren. 2009. “The

Changing Right to the City: Urban Renewal and Housing Rights in Globalizing

Shanghai and Mumbai” City & Community

8(4) December, American Sociological Association: 407-432.

No comments:

Post a Comment