A literature review on

employability with diagramming techniques

Joseph Kim-keung Ho

Independent

Trainer

Hong Kong, China

Abstract:

Literature review is an important exercise in

dissertation projects. Other than scholarly essay writing, using diagrams to conduct

literature review is also very useful for performing literature review. This

paper makes use of three diagramming techniques, namely, construction of a

system map, a mind map and a cognitive map, to complement scholarly writing for

a literature review on employability. The hands-on exercise of

diagramming-based literature review by the writer confirms the practical value

of doing so. In particular, a number of personal observations from such an

exercise by the writer contribute to our theoretical knowledge on the topics of

literature review and managerial intellectual learning. Readers interested in

the topic of employability should also find the literature review on

employability informative for research purpose.

Keywords:

diagramming, employability, literature review, managerial intellectual learning

Introduction

In

doing dissertation projects, literature review is an essential task, and one

which many tertiary education students have expressed to the writer, as part-time

teacher, tremendous difficulties to perform (Ho, 2015a). The writer has

previously attributed students’ difficulties to conduct literature review to

their managerial intellectual learning ineffectiveness (Ho, 2015a). In this

regard, one obvious way for students to overcome this problem is to learn how

to improve their managerial intellectual learning, on which there is an

established literature (see the Facebook page on Managerial Intellectual Learning). This paper makes another

contribution to the writer’s academic works on literature review and Managerial

Intellectual Learning by evaluating the practical value of diagramming

techniques for literature review. As a matter of fact, the relevance of the

diagramming techniques to literature review and Managerial Intellectual

Learning has been recognized in the Managerial Intellectual Learning topic,

notably for rendering images of knowledge structures. This paper is devoted to

this diagramming matter. Specifically, the writer presents a literature review

on employability and then makes use of diagramming techniques to render the

knowledge structure of employability. An evaluation of the experience of using

diagramming techniques for literature review is then carried out.

Basic ideas and study themes of

employability

The

topic of employability has been studied in quite a number of academic subjects,

such as business and management studies, human resource management, psychology,

educational science and career theory (Heijde and Heijden, 2006). At the same

time, different stakeholders hold different and evolving perceptions and

concerns on the employability topic. Consequently, there is an array of basic

ideas and study themes of employability, endorsing mildly different perspectives

and priorities of concerns. Based on the writer’s literature review on

employability, these ideas and study themes are reported in this section. They

are reviewed under the sub-titles of: (i) evolution of employability thinking,

(ii) definitions of employability, (iii) employability concerns and perceptions

of major stakeholders, and (iv) practices to improve employability.

Subtitle (i): evolution of

employability thinking: According to Cuyper,

Bernhard-Oettel and Bernston (2008), interest in employability appeared around

the 1950s, with major concern being employability interventions to promote

employment chiefly for the vulnerable groups, e.g., youngsters, the long-term

employed, or the disabled. In contrast, contemporary employability policy is

more comprehensive, essentially covering the whole working population (Cuyper,

Bernhard-Oettel and Bernston, 2008); such policy tends to stress enhanced

labour market flexibility, employee dynamic competence and entrepreneurship

(Haasler, 2013) in response to the prevailing trend of ever more flexible

employment arrangements and turbulent career environment (Fugate, Kinicki and

Ashforth, 2004). In this respect, employability in this postindustrial

knowledge society, dictates an individual’s familiarity with “the newest

technology” (Cuyper, Bernhard-Oettel and Bernston, 2008) and competence in

career self-management (i.e., to cultivate individual employability). Another

major thinking on employability is to multi-perspective to comprehend employability

at the individual, human resource management, and national workforce levels

(Cuyper, Bernhard-Oettel and Bernston, 2008). On the whole, there is no single universal

school of employability thinking as different countries promote somewhat

dissimilar employability policies and thinking.

Subtitle (ii): definitions of

employability: It has frequently been said that employability

is difficult to define (Sung et al.,

2013). Nevertheless, a number of definitions on employability, reflecting

diverse underlying perspectives, can be found in the literature. They include: (a)

“the individual’s

perception of his or her possibilities to achieve a new job” (Cuyper, Bernhard-Oettel and Bernstson, 2008), (b) “a

set of achievements – skills, understandings and personal attributes - that

make graduates more likely to gain employment and be successful in their chosen

occupations, which benefits themselves, the workforce, the community and the

economy” (Marais and Perkins, 2012), and (c) “a form of work specific active adaptability that enables workers to

identify and realize career opportunities” (Fugate, Kinicki and

Ashforth, 2004). In short, some definitions are more subjective in perspective

than others.

Subtitle (iii): employability

concerns and perceptions of major stakeholders:

It is well recognized that unemployment is “detrimental for health and

well-being” (Green, 2011). On the other hand, improved employability implies

improved ability “to find and sustain employment” (Green, 2011) and is

associated with career success (Heijden, Lange, Demerouti and Heijde, 2009) on

an individual’s part. Besides, improved employees’ employability enables

organizations to “meet fluctuating demands for numerical and functional

flexibility” (Heijden, Lange, Demerouti and Heijde, 2009). Conceptually, an

individual’s employability can be related to an enterprise’s competence via the

competence lens (Heijden, Lange, Demerouti and Heijde, 2009). Thus, both

employees and employers care about employability. Paradoxically, there is an

employer’s concern that strengthened employability of employees could weaken

employees’ “affective organizational commitment and performance” (Cuyper and

Witte, 2011). Another stakeholder group, higher education institutions, is also

attentive to their students’ employability as well as the associated interest

to “contribute to the economic development …of nations through the fostering

of…. human capital formation” (Laughton, 2011). Nevertheless, it has been

suggested that university professors and employers “tend to disagree on which

competences will qualify students best for their professional career” (Busch,

2009). In particular, while “employers tend to expect universities to provide

normative, vocational courses”, universities “see their duty as enabling their

students to take a critical stance on a variety of subjects” (Busch, 2009).

Such university view is echoed by Conlon (2008) who raises the apprehension in

the context of engineering education that “a focus on employability will not

equip engineers to be socially responsible because it fails to problematise the

current structure of work and society”.

Subtitle (iv): practices to improve

employability: Practices to improve employability are

recognized to involve a range of actors, e.g., employers, employees, students,

higher education institutions and the government (Haasler, 2013). Typical examples

of employability promotion practices include training, career counselling and

personal networking (Vanhercke et al.,

2015). In general, employability practices endorse (a) lifelong learning

(Haasler, 2013), (b) proactive and person-centered career management (Fugate,

Kinicki and Ashforth, 2004), (c) mastery of transferable skills, e.g.

management skills and generic employability skills[1], (d)

usage of national qualification frameworks for employability promotion (Sung et al., 2013) and (e) collaboration

between employers and universities in the forms of guest speakers, work

placements and consultancy projects (O’Leary, 2013). For universities,

employability promoting practices include embedding employability skills in

higher education curriculum (Stoner and Milner, 2010) and employment of

students as student ambassadors (Glendinning et al., 2011). Even so, different countries do adopt different

employability practices. For example, Singapore’s employability policy treats

employability promotion as “up-skilling workers for improving job performance

and income mobility” (Sung et al.,

2013); both the UK and Australia favour attempts to “mass-produce employability

skills” (Sung et al., 2013); finally

Germany’s employability policy emphasizes entrepreneurship and self-employment.

The

employability ideas and practices examined in the academic literature are grouped

under the four subthemes (i.e., subtitles (i) to (iv).) above. It needs to be

point out that these ideas and practices are not totally compatible with each

other and they also evolve over time in mildly different directions in

different countries. In short, as an outcome of the essay-based literature

review by the writer, the four subthemes reveal a somewhat chaotic intellectual

landscape on employability (also see Facebook page on employability) with diverse voices. On the other hand, it is

exactly this messy intellectual landscape that offers cogent conceptual

stimulation to inform academic studies in this subject domain. This subject

domain includes scholar-practitioner (Ho, 2014a; 2015b), managerial

intellectual learning, Multi-perspective, Systems-based (MPSB) Research (Facebook

page on Multi-perspective, Systems-based

Research) and literature review (Facebook page on literature review), which have been researched on by the writer and

which explicitly consider employability as one of their research topics. (Exactly

how the employability literature reviewing findings is able to contribute to

the theoretical development on scholar-practitioner, managerial intellectual

learning and the MPSB Research is not examined in this paper.) The next task is

to make use of diagramming techniques to conduct the second stage of literature

review on employability.

Diagramming on employability as

literature review

Literature

review, to Bryman and Bell (2007), is “where you demonstrate that you are able

to engage in scholarly review based on your reading and understanding of the

work of others in the same field as you”. In the words of Saunders et al., (2012), it provides the

foundation on which a research is built. In

this paper, three types of diagrams are employed to conduct the diagramming-based

literature review on employability. They are (a) a systems map (Open

University, 2016), (b) a mind map (Buzan and Buzan, 1995) and (c) a cognitive map

(Eden et al., 1983). The topic of

using these diagrams to conduct literature review has been explored by Ho (2014b)

in Multi-perspective, Systems-based Research. Altogether, three diagrams are

produced here, representing the results of the writer’s diagramming-based

literature review. Figure 1 is a system map.

Figure 2 is a mind map and, finally, Figure 3 is a cognitive map on

employability. Briefly a system map shows “the structure of a system of

interest” (Open University, 2016). A mind map is a visual way to organize

information around a core concept, with associated representations of ideas

(Buzan and Buzan, 1995). As to a cognitive map, it connects variables with

arrows indicating directions of influence so as to capture the systemic nature

among the chosen set of variables (Eden et

al., 1983). The writings on these maps are quite substantial and their

application scope is beyond that on literature review; interested readers are

referred to the bibliography for

further information on them. The three maps on employability are now shown as

follows:

Referring

to Figure 1 (a system map on employability

study), there are four components within the system boundary of employability study. The four components

correspond to the four employability subtitles that have been examined in the

previous section. The arrows within the system map broadly describe the logical

dependence among the four components. Figure 1 also identifies three elements

outside the system boundary, namely, (i) Managerial intellectual learning, (ii)

Multi-perspective, Systems-based Research and (iii) Real-life impacts. Their

presence in Figure 1 makes explicit the underlying research interest of the

literature review by the writer on employability. In short, the system map (re:

Figure 1) reveals more vividly the four employability subthemes and their

interrelatedness to each other as well as other related but out-of-scope

research interests.

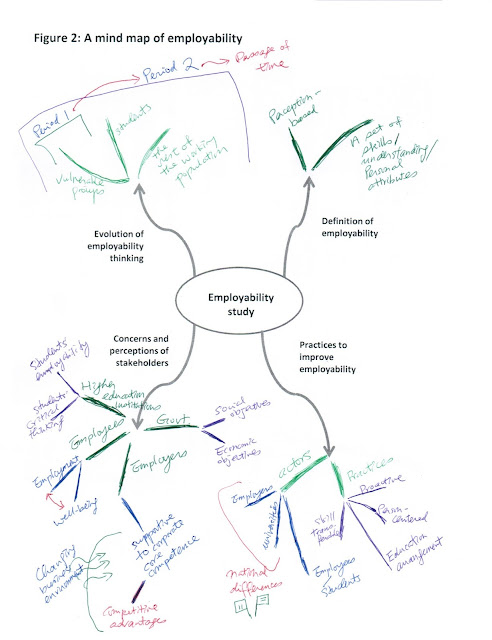

Regarding

Figure 2, a mind map of employability, the associated ideas of the four

employability subthemes are again shown. Different colours and arrows are

employed in the mind map to manifest the knowledge structure of employability

in a more engaging way. It makes the conceptual landscape of employability, as

described in the previous section, easier to grasp in one broad-brush picture,

especially in a group-based literature review session.

With

regard to Figure 3, a cognitive map of employability, a number of key variables

are chosen from the literature to form a set of interrelated variables. The

arrows in Figure 3 show the directions of influence among these variables. By

default, the arrows indicate positive correlations between the independent variables,

with outgoing arrows, (e.g., “understand transferable employability skills”)

and the dependent variables, with incoming arrows (e.g., “a better society”). [Note:

some variables have both incoming and outgoing arrows, e.g., “improved

employability” and “improved organizational performance”.] Some variables have

mutual causation with each other, which is indicated with a double arrow, e.g.

between “effective career self-management” and “effective life-long learning”. It

is also feasible to incorporate incompatible ideas in the same map, as there is

no requirement that all the variables need to reinforce each other to propel

the whole system toward one direction. In a nutshell, the cognitive map (re:

Figure 3) depicts the systemic (e.g., network-like) nature of the conceptual

landscape of employability in a comprehensible way.

An

overall assessment of the practical value of diagramming for literature review,

based on the writer’s hands-on experience here, is provided in the next section.

The practical value of diagramming

for literature review: some observations

Using

diagramming, e.g., subject trees and relevance trees (Saunders et al., 2012: chapter 3), for literature

review and intellectual learning is definitely not a novel idea. The hands-on

experience of using a system map, a mind map and a cognitive map by the writer

to conduct a literature review on employability, in this case, is a revisit to

this topic in the mainstream literature review subject. Nevertheless, due to

the writer’s specific research interest, its practical value for managerial

intellectual learning is explicitly stressed in this paper (re: Figure 1). More

specifically, the following five personal observations by the writer are made

on this diagramming exercise on employability:

Observation 1 – on resolution level:

The systems map offers a lower level of resolution on the employability subject

than the mind map and the cognitive map. Adding key words in the components of

the systems map is nevertheless also feasible.

Observation 2 – on perspective

expressiveness: The systems map projects a more

unitary (i.e., how-to) view on the employability subject than that of the mind

map and the cognitive map. On the other side, the mind map and the cognitive

map have higher ease to capture contrasting viewpoints in one map, thus more

expressive in pluralist and critical terms.

Observation 3 – on knowledge

structure forms: The systems map and the cognitive map

are more capable to express knowledge structures in various forms, e.g.,

network forms, while the mind map is good at expressing knowledge structures chiefly

in tree forms. In contrast, scholarly writing is less capable to stimulate

comprehension of intellectual ideas in a systemic way. Writing on a piece of

paper in essay form essentially encourages a linear form of reasoning.

Observation 4 – on stimulating and

engaging thinking: Diagramming techniques, e.g., systems

maps, mind maps and cognitive maps, are good complementary tools for essay-form

of literature review. They serve the purpose of clarifying, stimulating and

engaging thinking in literature review. On the other hand, scholarly writing

remains a critical endeavour in literature review, as it inevitably demands a

vigorous way to express line of reasoning with clear referencing.

Observation 5 – on group-based literature

review support: Very likely, the diagramming technique

is more relevant for group-based literature review, notably in the form of a

brainstorming or focus group session while scholarly writing is much less

engaging and stimulating for brainstorming and focus group-based literature

review.

As

a whole, the five personal observations on diagramming-based literature review

from the writer confirm the practical value of using diagramming techniques in

literature review. It also indicates good practical value of the diagramming

approach for promoting managerial intellectual learning, which necessarily

involves literature review efforts. Ultimately, the aim of doing both

essay-based and diagramming-based literature review together is, as Buzan and

Buzan (1995) put it, “to use… brain to its full potential”.

Concluding remarks

For

many of the writer’s students, literature review is conceived as a purely

academic exercise, only required to be performed during their academic study.

Otherwise, to them, literature review has no practical value to their workplace

practices. This writer argues against this constricted view. To this writer,

literature review is valuable to inform us on topics that we consider as

important in our daily life, such as employability. Via literature review, as

this paper demonstrates with one on employability, we are able to gain a deeper

and critical understanding of topics we care about. Because of that, literature

review is a critical skill for managerial intellectual learning; it enables us

to build up intellectual skills to address complex concerns that exist in the

real-world. One way or another, these concerns affect us. Literature review

unlocks, for its practitioners, the massive quality knowledge accumulated in

the scholarly works of the academic community. Moreover, the paper sheds light

on the practical value of diagramming-based literature review as complementary

exercises to the mainstream scholarly writing approach. Also, by clarifying

such practical value of diagramming for literature review and beyond, the paper

confirms the importance of diagramming-based literature review for managerial

intellectual learning, notably for knowledge structure construction in

diagrammatic forms. Exactly how the findings here can enhance managerial

intellectual learning theories should be examined in future research works.

Bibliography

Bryman, A. and E. Bell. 2007. Business Research Methods, Oxford University Press.

Busch, D. 2009. “What kind of intercultural competence will

contribute to students’ future employability” Intercultural Education 20(5) October, Routledge: 429-438.

Buzan, T. and B. Buzan, 1995. The mindmap book, BBC Books.

Conlon, E. 2008. “The new engineer: between employability and

social responsibility” European Journal

of Engineering Education 33 (2) May, Taylor & Francis: 151-159.

Cuyper, N.D., C. Bernhard-Oettel and E. Bernstson.

2008. “Employability and Employees’ Well-Being: Mediation by Job Insecurity” Applied Psychology 57(3): 488-509.

Cuyper, N.D. and H.A. Witte. 2011. “The

management paradox: Self-rated employability and organizational commitment and

performance” Personnel Review 40(2),

Emerald: 152-172.

Eden, C., S. Jones and D. Sims. 1983. Messing about in Problems: An informal

Structured Approach to their Identification and Management, Pergamon Press,

Oxford.

Facebook

page on Literature on literature review,

maintained by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address: https://www.facebook.com/literature.literaturereview/timeline).

Facebook

page on Literature on employability,

maintained by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address: https://www.facebook.com/Literature-on-employability-880896718687768/).

Facebook

page on Managerial Intellectual Learning,

maintained by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address: https://www.facebook.com/managerial.intellectual.learning/timeline).

Facebook

page on Multi-perspective, Systems-based

Research, maintained by Joseph, K.K. Ho (url address: https://www.facebook.com/multiperspective.systemsbased.research/timeline).

Fugate,

M., A.J. Kinicki and B.E. Ashforth. 2004. “Employability: A psycho-social

construct, its dimensions, and applications” Journal of Vocational Behavior 65, Elsevier: 14-38.

Glendinning,

I., A. Domanska and S.M. Orim. 2011. “Employability Enhancement through Student

advocacy” Innovation in Teaching and

Learning in Information and Computer Sciences 10(2), Routledge: 16-22.

Green,

F. 2011. “Unpacking the misery multiplier: How employability modifies the

impacts of unemployment and job insecurity on life satisfaction and mental

health” Journal of Health Economics

30, Elsevier: 265-276.

Haasler,

S.R. 2013. “Employability skills and the notion of ‘self’” International Journal of Training and Development 17(3), Wiley:

233-243.

Heijde,

C.M.V.D. and B.I.J.M.V.D. Heijden. 2006. “A competence-based and

multidimensional operationalizaion and measurement of employability” Human Resource Management 45(3) Fall, Wiley:

449-476.

Heijden, B.I.J.M.d., A.H.d. Lange, E.

Demerouti and C.M.V.d. Heijde. 2009. “Age effects on the employability-career

success relationship” Journal of

Vocational Behavior 74, Elsevier: 156-164.

A

theoretical review on the professional development to be a scholar practitioner

in business management”

Ho, J.K.K. 2015a.

“Examining Literature Review Practices and Concerns Based on Managerial

Intellectual Learning Thinking” International

Journal of Interdisciplinary Research in Science, Society and Culture 1(1):

5-19.

Ho, J.K.K. 2015b. “A survey study of perceptions on the scholar-practitioner notion:

the Hong Kong case” American Research

Thoughts 1(10) August: 2268-2284.

Laughton,

D.J. 2011. “CETL for employability: identifying and evaluating institutional

impact” Higher Education, Skills, and

Work-Based Learning 1(3), Emerald: 231-246.

Marais,

D. and J. Perkins. 2012. “Enhancing employability through self-assessment” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 46,

Elsevier: 4356-4362.

O’Leary,

S. 2013. “Collaborations in Higher Education with Employers and Their Influence

on Graduate Employability: An Institutional Project” Enhancing Learning in the Social Sciences 5(1) Taylor &

Francis: 37-50.

Open

University. 2016. “Systems Thinking and Practice: Diagramming” The Open

University, U.K. (url address: http://systems.open.ac.uk/materials/T552/)

[visited at April 25, 2016].

Saunders,

M., P. Lewis and A. Thornhill. 2012. Research

methods for business students, Pearson, Harlow, England.

Stoner, G. and M. Milner. 2010. “Embedding

Generic Employability Skills in an Accounting Degree: Development and

Impediments” Accounting Education: an

international journal 19(1-2) February-April, Routledge: 123-138.

Sung,

J., M.CM. Ng, F. Loke and C. Ramos. 2013. “The nature of employability skills:

empirical evidence from Singapore” International

Journal of Training and Development 17(3), Wiley: 176-193.

The

University of Nottingham and the University of Exeter. 2007. The Teaching, Learning and Assessment of

Generic Employability Skills February, the Centre for Developing and

Evaluating Lifelong Learning at the University of Nottingham and the South West

skills and Learning Intelligence Module at the University of Exeter, U.K. (url

address: http://www.marchmont.ac.uk/Documents/Projects/ges/ges-guide%5Boptimised%5D.pdf)

[visited at April 22, 2016].

Vanhercke, D., K. Kirves,

N.D. Cuyper, M. Verbruggen, A. Forrier and H.D. Witte. 2015. “Perceived

employability and psychological functioning framed by gain and loss cycles” Career Development International 20(2),

Emerald: 179-198.

[1] Generic

employability skills are “'transferable'

skills, independent of particular occupational sectors and organisations, which

contribute to an individual's overall employability by enhancing their capacity

to adapt, learn and work independently” (The University of Nottingham and the

University of Exeter, 2007).

No comments:

Post a Comment